Originally published in the Huffington Post

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/karri-jinkins/we-are-our-shadows_b_6149224.html

Karri Jinkins

Teacher, writer, actor, mom

We Are Our Shadows

The same year the Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize, 1989, I had my first panic attack. It was my freshman year in college and in the midst of hip-hop, frozen yogurt and scrunchies, I was celebrating independence from my parents for the first time but struggling academically. I had never defined myself as anxious, nervous or worried. Instead I was the girl who doesn’t worry about anything. That’s how my family had always described me, and I played the part well.

As I stood in the emergency room breathing into a bag, doctors urging me to go on medication for my anxiety, I began to question my own sanity. These panic attacks left me afraid to let anything or anyone touch me for fear I might succumb to more hallucinations. Had I finally become my mother, after being determined for so many years to be her opposite?

I shared with the doctors a history thick with mental illness in my family, and I privately realized I was traveling down a similar path. My mother had attempted suicide twice before I was born and again just after my birth. Her own mother struggled with sadness and depression and her maternal grandfather had hanged himself in his basement. My mother was extremely emotional and my father would often repeat to me and my four siblings, in a precautionary way, “Don’t upset your mother, or she’ll end up in the hospital again.” When I was a child, my mother did refer to a time when she had a nervous breakdown, but she never explained what that was. For most of my childhood, I imagined there were a bunch of nerve cells in her body that simply broke, shattered like glass falling from a table to the ground. I understood it to be a static event — not a perpetual state of being.

As a young child I was very attached to my mother. I was with her daily until I began kindergarten at age 5, and I loved being cuddled and sitting in her lap. She would often comment on how alike we were and she would apologize for that. I loved it when neighbors and friends would comment on how much I looked like her — how our eyes were the same shape and our skin was the same freckled shade of pinkish-white, and how we both sunburned easily. I competed with my older siblings for her attention, but as I grew older — like a person sleeping in a dark and windowless room but senses the sun setting — I began feeling something was not quite right with my mother.

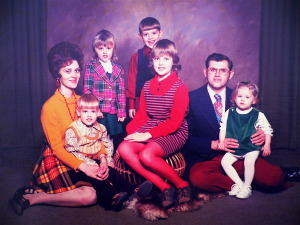

2014-11-13-P1020449.JPG

At 14 years old, I asked my eldest sister Laurie what a nervous breakdown was, and she described the night my mother put us all to bed and locked my father out of the house before she swallowed a bottle of Valium pills. Laurie also told me of previous attempts at suicide and of the shock treatments that my father believed had saved her life. I was sick to my stomach, thinking that my siblings and I came that close to being motherless. From that moment my view of my mother changed from seeing her as an emotionally fragile person to thinking of her as a crazy, mean, and selfish. I ran away from her fast, and my anger reached epic proportions that unconsciously remained locked inside me for years while I was determined to become more like my father and nothing like my mother. I got a job and submerged myself in art class, theatre as an escape. My mantra became, “l’ll never get married and I’ll never have children.” I thought that my mother’s life choices must have been the root cause of her mental illness. I was going to make different choices.

A few months after discovering the truth behind the nervous breakdown, I arrived home late after playing quarters with boys too old for me and I had an argument with my mother. I took a bottle of pills too — aspirin. I left a note, not expecting to see it in the morning, but a strong stomach meant I spent the next day in my bed throwing up. My parents debated taking me to the emergency room, but after much persuasion on my part and consultation with a family doctor, they decided to let me suffer on my own while they agonized about the whys. I could see the fear in my father’s blue eyes and the recognition in my mother’s face. I was embarrassed but recovered quickly, and I refused to acknowledge any genetic similarity to my mother’s condition.

When the panic attacks arrived that first year in college, I was obstinate about not going on medication. I began my search for alternatives. With luck on my side, my name had been picked out of a hat to a become part of the theatre department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Phillip Zarrilli taught a course named Asian discipline, and serendipitously I got a place in his class, too. He taught us Yoga, Tai-chi and an Indian martial art, Kalaripayattu. I learned about controlling by breath and my body and how these two instruments worked in conjunction with each other. Surprised, I watched the panic attacks go from daily to weekly, and eventually vanish all together. By the time I graduated, I rarely had one.

When I moved to New York directly after graduation I began to work furiously, and I rarely slept, burning the candle at both ends for years. I abandoned my yoga practice at first since I was far too busy to commit to anything so rigorous. Eventually the panic attacks started to come back, as well as major periods of debilitating depression.

Again, with a stroke of luck, I was interning at The Wooster Group in Soho, and actors Kate Valk and Willem Defoe both did yoga regularly. They inspired me to continue my own practice of it. As I slowly inched my way to a daily practice I eventually found a guru, and I ran off to India to study with him in secret hopes he might shed light on my sadness. It took me a few months to realize that he was not a magician. But yes, he was a healer, and a yogi who wasn’t afraid of his mind. He encouraged self- and ancestral-reflection. I meditated on my family history. I was the product of generations of strong but seemingly sad farmers on both sides — Norwegians, English, Scottish, and Germans who had come to America at the turn of the last century and had made many sacrifices to ensure the generations to come would have a better life. Life for me should have been much easier than for them, but why wasn’t it, at least not in my mind? The more I practiced yoga the more I sought answers until I was finally willing to admit the fact that my mother and her shadows were my shadows too, and they were scary. Not only had I been terrified that I might become my mother, I was terrified that a mother, any mother, could be capable of such behavior. I was protecting myself against my past and my future as a potential mother.

It wasn’t long after my self-discovery that I longed to come home and start living. After thousands of hours of yoga, marrying the man I thought I would never meet, and giving birth to a beautiful son, I see my life as a series of miraculous events. Each morning, often just before the sun rises, I peel myself out of my bed, I roll out my yoga mat and begin saluting the sun as it rises in the east in hopes of creating some new shadows for my son and his children.

It’s now been 20 years since I’ve had a panic attack. Although the depression continues, I work through it daily on my yoga mat — most days that works. My mother takes her daily dose of anti-depressant pills, and for the last 10 years I can’t remember seeing her so content. I love her patience and selflessness, and I strive to be like her more.

One day last summer, I was outside playing with my son and as the sun beamed down on our backs he pointed to our shadows on the pavement and said, “Mommy look, our shadows, they never leave us right? We are our shadows and our shadows are us, right?” Right.